Almonds: Growth of an Industry Contributes to California Water Woes

One gallon of water for every nut harvested/consumed-counter arguments from growers try to explain it away but no matter how we try to justify the growth/reach of this form of mono-culture tree farming-we’re doing it all wrong.

One gallon of water for every nut harvested/consumed-counter arguments from growers try to explain it away but no matter how we try to justify the growth/reach of this form of mono-culture tree farming-we’re doing it all wrong.

Industrial agriculture in California has been facing one crisis after another for more than a decade. Water battles between cities and rural farming areas has escalated as populations in cities increases and new mega-farms spring up across the Central Valley. Stakeholders in the allocation of water resources include not only cities and farms but precious watersheds where endangered species became endangered due to ever increasing water demands draining resources away from these habitats. Biodiversity has been greatly diminished as rainfall totals decrease and groundwater reserves are diverted to meet demand elsewhere.

The popularity of almonds with consumers has grown exponentially over the last few years. From the “milk” now sold on store shelves of large and small outlets to promotion by nutritionists citing it as a super food, supply has grown to meet the demand. Almond plantations began replacing conventional vegetable production as farmers try to cash in on the newest demands from the market. And at almost the same time severe drought hit the greater part of the state.

“California’s drought-stricken Central Valley churns out 80 percent of the globe’s almonds, and since each nut takes a gallon of water to produce, they account for close to 10 percent of the state’s annual agricultural water use—or more than what the entire population of Los Angeles and San Francisco use in a year.” (New Republic)

There is no doubt that California’s water problems have been exacerbated with the exponential growth of commercial almond farming. As climate scientists began to look at all aspects of this new crisis and calculate water usage across the spectrum and almonds didn’t fare too well. Environmental groups picked up on this fact and began an information campaign to make the consuming public aware of how their choices were connected to the growing water crisis.

As more attention was given to these facts the growers became increasingly vocal in denying these allegations, citing that those numbers were based solely on the total number of nuts produced for consumption, when in fact hulls, shells, and even the trees, dead or dying, should be part of these calculations.

Well, let’s look at that first rebuttal. Undoubtedly, the real cash value for farmers is the nut but they also helped to create a supply market for the previously unmarketable byproducts. Shells are ground up to produce fireplace logs, hulls have become feed for dairy cattle, and dead or dying trees are cut and co-fired with coal to produce energy. They even go so far as to take credit for cleaning the air because they claim that the trees act as carbon storage.

On this last point from growers, let’s make it clear that these trees don’t live long enough to accumulate any significant carbon dioxide, so that argument is moot. Besides the fact that burning shells and dead and dying trees for energy production and the fossil fuels consumed in the production and transportation of almonds and their byproducts all add up to exponentially more carbon emitted than sequestered.

Another pesky fact we can’t ignore is that almond trees have to be watered all year long, drought or not, or they will die taking with them all future profits. It takes at least five years from planting to harvest so if there was a significant die off millions of dollars of profit would be lost.

These issues have been brewing for several years. As growers of vegetables and fruits decided to get in on the lucrative nut market, hundreds of thousands of acreage once producing tomatoes, carrots, and peppers, now contain huge almond groves.

California is the nation’s leading producer of almonds, avocados, broccoli, carrots, cauliflower, grapes, lettuce, milk, onions, peppers, spinach, tomatoes, walnuts, and dozens of other commodities, according to a 2012 Department of Agriculture report (PDF). The state produces one-third of our vegetables and two-thirds of our nuts and fruits each year. While fields in iconic agricultural states like Iowa, Kansas, and Texas primarily produce grain (most of which is used to fatten animals), pretty much everything you think of as actual food is grown in California. Simply put: We can’t eat without California. But as climate change–fueled droughts continue to desiccate California, the short-term solution from farmers has been to double down on making money. (Slate-2015)

Which brings us back to the issue of burning almond shells and dead trees for energy. Since 2015 biomass burning facilities have been going under at a steady pace being replaced by government subsidized solar farms amid the fields and orchards of the San Joaquin Valley. Once installed these solar arrays take little investment to maintain and continue to pay benefits long after their initial cost is recouped.

Biomass burning as a supplemental energy producing resource was heavily subsidized in the mid-70s due to the oil shortages created by OPEC reducing production- but those subsidies have largely expired and are now being applied to solar and wind energy generation.

There is no way to correctly predict what the cost of solar will be in the coming years. What we can say is that there are many reasons to pursue non-combustive forms of energy production in the future. This means, for almond farmers that their shells and dead trees may not have the market demand they counted on for large profit margins.

What needs to happen now is a giant systems shift-away from extraction and burning of organic matter for energy production. We can do this now, while we still have options, or we can wait til there is no alternative and the infrastructure needed to transition will take years to build and implement. In the meantime, power/energy is limited, crop shortages destroy food sovereignty across the country and most likely the world as the climate changes rapidly. We are ill-prepared now to provide food, shelter, power, and clean/safe drinking water to Puerto Rico, Houston, and southern Florida after the devastating storms that ravaged these areas. With ever-increasing storm intensity and damage we can only predict that many more people will suffer and die if we don’t get our collective act together and find real solutions for the pending mega-shift coming soon.

One gallon of water for every nut harvested/consumed-counter arguments from growers try to explain it away but no matter how we try to justify the growth/reach of this form of mono-culture tree farming-we’re doing it all wrong.

Almond Facts:

1. Most of our almonds end up overseas. Almonds are the second-thirstiest crop in California—behind alfalfa, a superfood of sorts for cows that sucks up 15 percent of the state’s irrigation water. Gizmodo’s Walker—along with many others—wants to shift the focus from almonds to the ubiquitous feed crop, wondering, “Why are we using more and more of our water to grow hay?” Especially since alfalfa is a relatively low-value crop—about a quarter of the per acre value of almonds—and about a fifth of it is exported.

It should be noted, though, that we export far more almonds than alfalfa: About two-thirds of California’s almond and pistachio crops are sent overseas—a de facto export of California’s overtapped water resources.

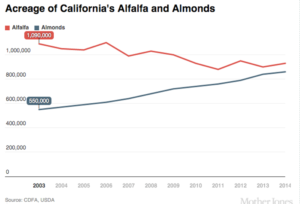

2. While alfalfa fields are shrinking, almond fields are expanding—in a big way. The drought is already pushing California farmers out of high-water, low-value crops like alfalfa and cotton, and into almonds and two other pricey nuts, pistachios and walnuts. This year, California acreage devoted to alfalfa is expected to shrink 11 percent, and cotton acres look set to dwindle to their lowest level since the 1920s.

3. Unlike other crops, almonds always require a lot of water—even during drought. Annual crops like cotton, alfalfa, and veggies are flexible—farmers can fallow them in dry years. That’s not so for nuts, which need to be watered every year, drought or no, or the trees die, wiping out farmers’ investments.

Already, strains are showing. Back in 2013, a team led by US Geological Survey hydrologist Michelle Sneed discovered that a 1,200-square-mile swath of the southern Central Valley—a landmass more than twice the size of Los Angeles—had been sinking by as much as 11 inches per year, because the water table had fallen from excessive pumping. In an interview last year, Sneed told me the ongoing exodus from annual crops and pasture to nuts likely played a big role.

4. Some nut growers are advocating against water regulation—during the worst drought in California’s history. “I’ve been smiling all the way to the bank,” one pistachio grower told the audience at the Paramount event, according to the Western Farm Press account. As for water, that’s apparently a political problem, not an ecological one, for Paramount. “Pistachios are valued at $40,000 an acre,” Bill Phillimore, executive vice president of Paramount Farming, reportedly told the crowd. “How much are you spending in the political arena to preserve that asset?” Apparently, he meant: protect it from pesky regulators questioning your water use. He “urged growers to contribute three-quarters of a cent on every pound of pistachios sold to a water advocacy effort,” Western Farm Press reported.

5. Mostly, it’s not small-scale farmers that are getting rich off the almond boom. With their surging overseas sales, almonds and pistachios have drawn in massive financial players hungry for a piece of the action. As Mother Jones reported last year, Hancock Agricultural Investment Group, an investment owned by the Canadian insurance and financial services giant Manulife Financial, owns at least 24,000 acres of almonds, pistachios, and walnuts, making it California’s second-largest nut grower. TIAA-CREF, a large retirement and investment fund that owns 37,000 acres of California farmland, and boasts that it’s one of the globe’s top five almond producers.

Then there’s Terrapin Fabbri Management, a private equity firm that “manages more than $100 million of farm assets on behalf of institutional investors and high net worth clients” and says it’s “focused on capitalizing on the increasing global demand for California’s agricultural output.” In a piece earlier this year, The Economist pointed out that Terrapin had “bought a dairy company and some vineyards and tomato fields in California, and converted all to grow almonds, whose price has soared as the Chinese have gone nuts for them.” The magazine added that “such conversions require up-front capital”—e.g., to drop wells—”and the ability to survive without returns for years.” Those aren’t privileges many small-scale farmers enjoy.

This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here to present detailed facts – and us not having to expend resources and give credit to the independent journalists at Mother Jones.